Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is a highly prevalent disease worldwide, with more than 1.4 million new cases each year1. According to GLOBOCAN, in 2020, there were 14,460 new cases of PCa in Colombia, with an age-standardized incidence rate of 49.8/100,000 men1. In relation to its high prevalence, PCa is a public health priority in national cancer control plans. However, persistent clinical gaps, barriers in health care, and low awareness of the disease have paved the way for three out of ten men with PCa to be diagnosed in advanced stages of the disease2.

Men diagnosed in metastatic stages and those who progress after receiving treatment with radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy are grouped into a stage known as metastatic hormone-sensitive PCa (mHSPC)3. Appropriate treatment of these patients can delay progression to metastatic castration-resistant PCa (mCRPC), a surrogate for overall survival (OS). In one study, the 2-year OS rate of patients with mHSPC who progressed within 6 months of diagnosis was 42% compared to 89% in patients who did not progress as rapidly4.

At least eight clinical trials have demonstrated that treatment intensification delays mCRPC progression and has a clear impact on OS with a consistent reduction in the risk of death of about 30%5–4. However, although its clinical and economic utility has been demonstrated and it has shown gains in quality-adjusted life years with therapies added to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)5, the adoption of intensification worldwide has been slow, due to a possible lack of knowledge of this stage of the disease and the efficacy of the treatment.

In Colombia, there is limited knowledge of mHSPC, so this systematic review aims to explore the landscape of the disease, diagnosis, and treatment patterns in the Colombian context.

Method

An exhaustive systematic literature review (SLR) was carried out following the reporting recommendations of the PRISMA guidelines6. PubMed, Embase, Cochrane database of systematic reviews, Lilacs (virtual health library), Scielo, Redalyc, and national administrative databases, among others, were consulted. The search strategies were designed using the terms MeSH, Emtree, and DECs, free language, synonyms, abbreviations, acronyms, spelling variations, and plurals (Supplementary data). A manual “snowball” search was carried out by reviewing the list of bibliographic references of the selected studies.

Studies that addressed the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of mHSPC in Colombia were included, without a date limit, in English or Spanish, published, in the press, grey literature, or even in summary format if they provided information of interest. Studies that did not provide precise information or that might be biased were excluded from the study. In addition, all the information available from the national administrative databases and other sources was included.

Two investigators independently reviewed the titles and/or abstracts of the retrieved studies. Any disagreement between them about the eligibility was resolved by consensus. Afterward, each publication was reviewed in full text to verify that it met the eligibility criteria. The information was extracted according to the pre-established topics, including additional references if the evidence provided by each publication was complementary.

According to the nature of the information, the results are presented as a narrative review on different topics, as follows: epidemiology, economic burden, diagnosis, and treatment. It was not possible to synthesize the information quantitatively due to the nature and heterogeneity of the data.

Results

A total of 1574 references were identified from searches of the PubMed (n = 630), Embase (n = 575), Cochrane Library (n = 335), Scielo (n = 6), and Lilacs (n = 25) databases, and three references were identified by manual search. After removing duplicates, 1157 references were obtained. A total of 921 references were excluded after reading the title and abstract. A total of 236 full-text manuscripts were evaluated, and 87 were selected for information extraction (Supplementary data). In addition, information was extracted from administrative databases and other sources that reported epidemiological data and treatment patterns of mHSPC in Colombia.

Epidemiology

In Colombia, there are five population-based cancer registries recognized by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, which provide high-quality data on cancer incidence and mortality1. However, these registries do not provide details regarding stage, diagnosis, or treatment.

The sources of information available on cancer in Colombia record widely different data. According to GLOBOCAN, in 2020, 14,460 new cases of PCa were diagnosed in Colombia, with an age-standardized incidence rate of 49.8/100,000 men, being the second most frequent cancer in general and the most common among men (27.4% of all new cases of male cancer)1. According to data from the Social Protection Integrated Information System (SISPRO) adopted by the Ministry of Health of Colombia for the compilation of comprehensive information on the Colombian health system, a total of 43,862 patients with PCa were identified for the period 2015-2019, with an estimated prevalence of PCa in the country of 454 cases/100,000 inhabitants, using men over 35 years of age as the denominator7. This source did not report information by stage at diagnosis or clinical subgroups.

According to the information from the high-cost account (CAC), which is based on the self-report of the institutions involved in patient care, by 2020, the incidence of PCa was 11.34 (10.90-11, 78)/100,000 men with a prevalence of 178.66/100,000. In this source, 78% of the cases had information about stage, the invasive ones corresponded to 99.48% and 28.38% to Stage IV (invasion to lymph nodes, bone or other organs according to tumor, node and metastasis classification, out of the total of cases with staging reported)8. However, due to the nature of the CAC data, it is considered that there may be underreporting, and it is not possible to rule out information bias, especially in the data regarding the stage and treatments9.

As mentioned, the current data for Colombia do not include differentiation by hormonal sensitivity or metastasis status. Thus, in an estimate based on the data available from the CAC, the de novo cases in the metastatic stage range between 2.95 and 4.24 cases/100,000 men (Table 1).

Table 1. Incidence estimates of mHSPC in Colombia based on data from CAC 2021 and Globocan 2020

| Source | Number of new cases* | Crude rate** | Adjusted rate*** |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAC | 760 | 3.09 | 2.95 |

| Globocan 2020 | 1052 | 4.34 | 4.24 |

|

*Includes only new cases reported by the CAC. ** Reported by 100,000 men. *** Based on data from Globocan 2020. Source: Own estimates based on CAC24 and Globocan 20202 data. |

|||

The other group of men with mHSPC is those detected in previous stages and who are not in ADT at the time of metastasis20. Regarding this group of men with mHSPC, there are no specific or comparable data for the country.

There are no reports from population sources about national mortality from mHSPC. Only one study was identified from one center that included 404 patients between 2007 and 2012 and reported for men with Stage IV PCa a survival of 52% at 5 years and 32% at 10 years, significantly lower than in non-metastatic states of the disease21.

No studies or information related to the burden of the disease in patients with mHSPC were identified in Colombia.

Economic burden

The development of mHSPC has been associated with considerable costs, particularly higher in de novo patients than in those who progress from a localized disease. Direct health care costs for all causes in patients with mHSPC increased 2-4 times after metastasis, increases that became evident several months before metastasis is diagnosed22.

In our context, a study determined the direct costs of managing patients with metastatic PCa23. The mHSPC stage had a lower annual cost than the mCRPC stage (US $15,030 vs. US $24,590, respectively), with a difference of US $9,559. The event that generated the greatest impact on the cost was the incidence of bone events associated with metastasis of the disease (55%). Advanced castration-resistant metastatic stages require greater use of resources associated with the management of the disease. The authors concluded that slowing or halting the progression of the disease toward castration resistance could reduce the annual costs of treatment for patients by more than half.

Treatment

At present, combined systemic therapy is the standard treatment for men with mHSPC. Patients should be treated with ADT in combination with last-generation hormonal agents (novel hormonal therapies [NHT]), such as abiraterone acetate with prednisone or docetaxel (DOC) (chemo-hormonal therapy) or with second-generation antagonists of the androgen receptor (enzalutamide or apalutamide)24. Furthermore, there is evidence of efficacy with combination therapy including abiraterone, enzalutamide or darolutamide plus DOC and ADT.

The benefit of ADT has been widely documented; however, eventually, patients will progress to castration-resistant disease, in which they have a worse prognosis in terms of quality of life and survival. The last decade has shown the results of randomized clinical trials that highlight the role of additional therapy with chemotherapy and NHT in terms of progression-free survival and OS in scenarios of hormone-sensitive metastatic disease (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of the randomized clinical trials for the management of mHSPC

| Description | GETUG- AFU 15 (%) | CHAARTE D (%) | STAMPEDE arm C (%) | LATITU DE (%) | STAMPEDE arm G (%) | PEACE-1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Gravis et al. | Kyriakopoulos et al. | Clarke et al. | Fizazi et al. | James et al. | Fizazi et al. |

| Year | 2013-2016 | 2018 | 2019 | 2013-2014 | 2019 | 2022 |

| Agent under study | DOC 75 mg/m2 | DOC 75 mg/m2 | DOC 75 mg/m2 | ABI 1000 mg | ABI 1000 mg | ABI 1000 mg |

| Control therapy | ADT | ADT | ADT | ADT | ADT | Standard therapy ± RT |

| Inclusion criteria | mHSPC, without prior CMT | mHSPC, without prior CMT | mHSPC, without prior CMT | mHSPC high risk b, without CMT or previous surgery | mHSPC or nodes+or 2 RF or high risk of relapse to | mHSPC de novo |

| Functional status | Karnofsky≥70 | ECOG 0-2 | WHO 0-2 | ECOG 0-2 | WHO 0-2 | ECOG 0-2 |

| Primary outcome | OS | OS | OS | OS, rPFS | OS | OS, rPFS |

| No. control/trea tment patients | 193/192 | 393/397 | 724/362 | 602/597 | 502/500c | 589/583 |

| Median follow-up, months | 84 | 54 | 78 | 52 | 73c | 45.7 |

| Age, years Median (range) control versus treatment | 64 (58-70) versus 63 (57-68)d | 62 (39-91) versus 64 (36-88) | 65 (60-71) versus 65 (62-70)d | 67 (± 9) versus 67 (± 9) | 67 (39-83) versus 67 (42-85)a | 66 (IQR 59-70) versus 66 (IQR 60-70) |

| PSA, ng/ml Median (range) control versus treatment | 25.8 (5.0-126) versus 26.7 (5.0-106)d | 52.1 (0.1-8056) versus 50.9 (0.2-8540) | 103 (33-338) versus 97 (38-348)d | – | 56 (0-10530) versus51 (0-21460)a | NA |

| Gleason 8-10 control versus treatment | 59 versus 55 | 62 versus 61 | 68 versus 69 | 97 versus 98 | 75 versus 74a | NA |

| Bone metastases control versus treatment | 81 versus 81 | – | 87 versus 83 | 87 versus 98 | 47 versus 45a | NA |

| Control versus treatment visceral metastases | 12 versus 15 | 17 versus 14 | 13 versus 12 | 22 versus 22 | 6 versus 4a | NA |

| High volume disease control versus treatment | 47 versus 48 | 64 versus 66 | 57 versus 54 | 78 versus 82 | 48c | 65 versus 63 |

| CMT after control versus treatment | 0 versus 0 | 0 versus 0 | 0 versus 0 | 0 versus 0 | 0 versus 0a | NA |

| OS HR (95% CI) control versus treatment | 0.88 (0.68-1.14) | 0.61 (0.47-0.80) | 0.81 (0.69-0.95) | 0.66 (0.56-0.78) | 0.60 (0.50-0.71)c | 0.82 (0.69-0.98) |

| OS, months. Median (95% CI) control versus treatment | 48.6 (40.9-60.6) versus 62.1 (49.5-73.7) | 47.2 (41.8-52.8) versus 57.6 (52.0-63.9) | 43.8 (NA) versus 58.5 (NA) | 36.5 (33.5-40.0) versus 53.3 (48.2-NR) | 45.6 (NA) versus 79.2 (NA) | NA |

| OS in low-volume mHSPC. Control versus treatment | 1.02 (0.67-1.55) | 1.04 (0.70-1.55) | 0.76 (0.54-1.07) | 0.72 (0.47-1.10h) | 0.55 (0.41-0.76c) | NA |

| OS in high- volume mHSPC. Control versus treatment | 0.78 (0.56-1.09) | 0.63 (0.50-0.79) | 0.81 (0.64-1.02) | 0.62 (0.52-0.74h) | 0.54 (0.43-0.69c) | NA |

| rPFS Control versus treatment | 0.69 (0.50-0.75) | 0.61 (0.55-0.87) | 0.66 (0.57-0.76f) | 0.31 (0.27-0.36g) | 0.31 (0.26-0.37a,f) | 0.54 (0.44-0.67) |

| Description | ARCHES (%) | ENZAMET (%) | TITAN (%) | ARASENS (%) | SWOG 1216 (%) | STAMPED E arm H (%) |

| Reference | Armstrong et al. | Davis et al. | Chi et al. | Smith et al. | Agarwal et al. | Pärker et al. |

| Year | 2019-2022 | 2019 | 2021 | 2022 | 2022 | 2018 |

| Agent under study | ENZA 160 mg | ENZA 160 mg | APA 240 mg | DARO 600 mg | Orteronel (TAK-700) 300 mg | RT |

| Control therapy | PBO+ADT | NSAA | PBO+ADT | PBO+DOC+ADT | ADT with BIC | ADT |

| Inclusion criteria | mHSPC | mHSPC 2 previous DOC cycles allowed | mHSPC 6 previous DOC cycles allowed | mHSPC | mHSPC | mHSPC C |

| Functional status | ECOG 0-2 | ECOG 0-2 | ECOG 0-1 | ECOG 0-1 | Zubrod 0-3 | WHO 0-2 |

| Primary outcome | OS | OS | OS, rPFS | OS | OS | OS |

| No. control/trea tment patients | 576/574 | 562/563 | 527/525 | 655/651 | 641/638 | 1029/1032 |

| Median follow-up, months | 14.4 | 34 | 23 | 43 | 57 | 37 |

| Age, years Median (range) control versus treatment | 69.5 (46-92) | 69 (64-75) versus 69 (63-75) d | 68 (43-90) versus 69 (45-94) | 67 (42-86) versus 67 (41-89) | 68 | 68 (37-86) versus 68 (45-87) |

| PSA, ng/ml Median (range) control versus treatment | – | – | 4 (0-2229) versus6 (0-2682) | NA | 31,8 (2-6.651) versus27,2 (2-6,710) | 98 (30-316) versus 97 (33-313) |

| Gleason 8-10 control versus treatment | 66 | 57 versus 60 | 68 versus 67 | 78.9 versus 77.6 | 59,6 versus 58,3 | 83 versus 82 |

| Bone metastases control versus treatment | 84.4 | 82 versus 80 | 100 versus 100 | 79.5 versus 79.4 | 75,2 versus 73,7 | 89 versus 89 |

| Control versus treatment visceral metastases | 4.9 | 12 versus 11 | 15 versus 11 | 18 versus 17.1 | 13.4 versus 15.4 | 9 versus 10 |

| High volume disease control versus treatment | 63.2 | 52 versus 53 | 64 versus 62 | Not applicable | 48,8 versus 48,6 | 58 versus 57 |

| CMT after control versus treatment | NA | 52 versus 53 | 10 versus 11 | NA | NA | NA |

| OS HR (95% CI) control versus treatment | 0.66 (0.53-0.81) | 0.70 (0.58-0.84) | 0.65 (0.53-0.79) | 0.68 (0.57-0.80) | 0.86 (0.72-1.02) | 0.68 (0.52-0.90) |

| OS, months. Median (95% CI) control versus treatment | NR | 73.2 (64.7-NR) versus NR | 52.2 (41.9-NR) versus NR | 48.9 (44.4-NE) versus NE | 70.2-81.1 | 41.6 versus 42.5/DM 1.0 (−0.6 a 2.5) |

| OS in low-volume mHSPC. Control versus treatment | NA | 0.43 (0.26-0.72) | 0.67 (0.34-1.32) | NA | NA | 0.68 (0.52-0.90) |

| OS in high- volume mHSPC. Control versus treatment | NA | 0.80 (0.59-1.07) | 0.68 (0.50-0.92) | NA | NA | 1.07 (0.90-1.28) |

| rPFS Control versus treatment | 0.63 (0.52-0.76) | 0.40 (0.33-0.49) | 0.48 (0.39-0.60) | 0.36* (0.30-0.42) | NA | NA |

|

a Inclusion criteria included metastatic and non-metastatic disease. Risk characteristics: stage T3/T4 or PSA > 40 ng/m or Gleason score 8-10. High-risk criteria for relapse after RP or RT: PSA > 4 ng/m and doubling time < 6 months or PSA > 20 ng/mL in metastatic relapse or < 12 months of total treatment with ADT and interval > 12 months without treatment with ADT before enrollment. b Two of the following high-risk criteria: Gleason score 8, 3 bone metastases, 1 visceral metastasis. c According to the update of the STAMPEDE arm G. dInterquartile range. e Clinical PFS. f Failure-free survival (any type of progression). g PSA progression-free survival. h According to the LATITUDE update. i Time to castration resistance. NR: not reached; NA: not available; NE: not estimable; NSAA: non-steroidal antiandrogens; OS: overall survival; rPFS: radiographic progression-free survival; DOC: docetaxel; ABI: abiraterone; ENZA: enzalutamide; APA: apalutamide; DARO: darolutamide; ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; PBO: placebo; BIC: bicalutamide; RT: radiotherapy; CMT: chemotherapy; PSA: prostate-specific antigen. |

||||||

In the daily practice of countries with limited resources, therapeutic decisions can be variable in consideration of the costs of the therapies as well as their effectiveness. A large consensus of physicians specializing in cancer management in developing countries analyzed these decisions in context25. In de novo mHSPC with low-volume disease, options considered best practices included continuous ADT with luteinizing hormone releasing hormone agonist with or without first-generation androgen receptor antagonist or continuous ADT with abiraterone. In a context of limited resources, the same panelists opted for orchiectomy alone, considered a more cost-effective option26. In de novo mHSPC with high-volume disease, the best practices were considered ADT with abiraterone or with DOC, the latter option being the most appropriate given the limitation of resources.

Based on the available evidence, ADT should not be offered alone unless life expectancy is limited, or comorbidities make treatment unsafe. The selection of chemotherapy over second-generation antiandrogens depends on the different toxicity profile of the interventions, the characteristics of the patient, including comorbidities, compliance and preference, the duration of treatment, availability of hormonal therapies and generics drugs, and costs related. Chemotherapy lasts 18 weeks and is more cost-effective, with intense but short-lived toxicity. Second-generation antiandrogens are continued until disease progression, are more expensive and have ongoing long-term toxicities, such as bone loss, falls, hypertension, and adverse cardiovascular events27. Thus, the selection of therapy in mHSPC is an inpidualized decision based on considerations of the patient, the disease (volume, metastasis status), the treatment and the availability of resources. The early participation of a multidisciplinary team is desirable in the context of PCa for inpidualized care and an adequate assessment of available therapeutic options28.

Treatment patterns for mHSPC in Colombia

For the Colombian context, the information regarding PCa therapy is scarce. According to reports from the CAC, for metastatic stage in newly diagnosed patients, the prescription of systemic therapy (chemotherapy and others in 37.44%) predominates, followed by radiotherapy (34.11%) and surgery (17.01%). Regarding medications, the most frequent prescriptions for PCa in the country are leuprolide (47%), bicalutamide (32%) and goserelin (29%), followed to a lesser extent by DOC (10%) and enzalutamide and abiraterone (6% in total). However, no specific data are reported on mHSPC therapy8.

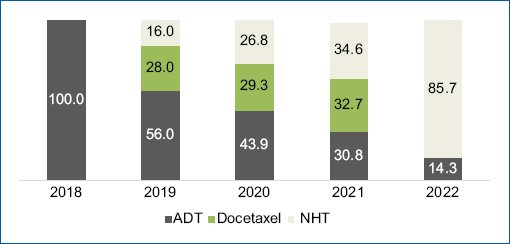

Based on SISPRO data, internal sponsor information, and gray literature, the proportion of mHSPC among all PCa patients is estimated to be between 20 and 30% depending on the practice setting. As reported in a study conducted in a highly complex referral center in the country, the diagnosis of mHSPC has increased in recent years, and treatment patterns have changed. Five years ago, 100% of patients were treated with ADT alone, and its frequency of use decreased over time. By 2022, only 14.3% of patients with mHSPC received this therapy, and the vast majority were receiving treatment with a NHT29 (Fig. 1). However, this scenario is not the same in all institutions that treat patients with mHSPC. In those of less complexity, intensification is carried out in approximately 70% to 80% of patients with mHSPC, with DOC in 60-70% of cases and with NHT in 30-40%30.

Figure 1. Treatment patterns of mHSPC in a highly complex referral center in Colombia. Source: Taken from Arenas Hoyos J. Treatment patterns in hormone-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer: Data from a highly complex referral center in Colombia. Real World Study. [Bogotá]: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana; 2022.

Discussion

The information available in our country about mHSPC is scarce. GLOBOCAN estimates cancer incidence at the national level based on incidence and mortality data from specific population registries7,31. However, there is no information regarding the stage of the disease, and the information available is highly dissimilar between the sources, which limits an adequate characterization of the disease.

According to data from the CAC, by 2021 in Colombia, 40.1% of PCa cases were diagnosed in a locally advanced or advanced stage, with a higher proportion in rural regions and the subsidized regime32. Unfortunately, there are no implemented public health strategies for PCa screening that could help to reduce the late diagnosis in the country. This is important because the diagnosis of PCa in the early oligometastatic environment is critical since the early initiation of systemic therapy improves the prognosis of these patients. Access barriers to high-quality methods for diagnosing and evaluating patients, such as tomography and bone scans, prostate-specific membrane antigen -, positron emission tomography magnetic resonance imaging, and radiotherapy, must be approached appropriately33.

In patients with mHSPC, disease progression imposes a considerable clinical burden. Studies in different populations have determined the time of evolution from mHSPC to a castration-resistant stage to be 12-23. 7 months, with wide variations according to the Gleason score, volume of the disease, and the number of metastases34. In patients with mHSPC, progression within 6 months of combined therapy has been reported as the best surrogate for OS4. The 2-year OS rates for patients who progressed within 6 months of randomization were 42% versus 89% for the patient population who did not progress as rapidly4. In the analysis by Hussain et al.35 prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression, defined as an increase of ≥ 25% greater than the nadir and an absolute increase of at least 2 or 5 ng/mL, was shown to predict OS in patients with HSPC and CRPC (p < 0.001), with a 2.4 times higher risk of death and a more than 4 times increased risk of dying if PSA progression occurred in the first 7 months. In historical analyses, median OS of 10 months versus 44 months has been reported in patients who had or did not have PSA progression at 7 months, hence the importance of this outcome as a surrogate for OS.

OS in men who start with mHSPC and receive treatment with ADT has been calculated in clinical trials at a median of 4 years5,9, being lower in those with high volume disease with a median survival of approximately 3 years5. Survival may be longer in those with hormone-sensitive metastatic recurrence, close to 4.5 years in high-volume disease and up to 8 years in low-volume disease. In addition, in men with low-volume mHSPC, the presence of non-regional lymph node metastases and concomitant bone metastases is a poor prognostic factor, although the survival of men with visceral metastases is worse36.

The addition of NHT or DOC to ADT was shown to increase the resistance to castration-free survival with a decrease in the risk of development of resistance to castration by 53%37. In addition, strong evidence from Phase 3 studies supports the benefit of current systemic therapeutic options on health-related quality of life outcomes. The addition of chemotherapy with DOC has been shown to prolong survival and delay disease progression in mHSPC. Targeted therapy with abiraterone also demonstrated improvements in OS of 38% and 37%, respectively, in the LATITUDE8 and STAMPEDE arm G9 studies compared to ADT alone. Subsequently, next-generation androgen receptor inhibitors improved the prognosis of mHSPC compared to ADT or non-steroidal antiandrogens. Enzalutamide demonstrated a 34% improvement in OS (ARCHES10) with a 60% reduction in progression or death during therapy (ENZAMET1). Similarly, apalutamide (TITAN2) showed improvements in OS versus ADT alone, as did darolutamide (ARASENS3) and abiraterone (PEACE-17) in combination treatment with ADT and DOC. According to analyses based on the volume of the disease (defined by CHAARTED), systemic chemotherapy based on taxanes seems to be more beneficial for those patients who present a high volume metastatic disease burden, whereas, with hormonal agents, better survival was reported regardless of volume. Recently, the NCCN guidelines changed the recommendation regarding the use of NHT and DOC in mHSPC, and the preferred treatment regimens include combination therapy with ADT and one of the following: abiraterone, apalutamide or enzalutamide or ADT plus DOC and one of the following: abiraterone or darolutamide. DOC only with ADT without a NHT is no longer an option of treatment in this scenario24.

Although ADT in combination with DOC or NHT has been shown to improve OS compared to ADT alone in patients with mHSPC for approximately a decade, real-life information obtained from administrative databases shows that these patients frequently do not receive these therapies. In the United States through 2021, only 36% of newly diagnosed patients received intensification of treatment. ADT alone remained the primary treatment of choice, with 50% of patients receiving ADT monotherapy and another 24% receiving an additional first-generation antiandrogen. In 7% of men, chemotherapy was used as a first-line treatment, leaving most men without a second agent to prolong life. A decrease in the intensification of treatment with NHT and chemotherapy was also observed in older men. This is concerning, as combination therapy is currently the standard of care, especially in patients with high-volume mHSPC38. This scenario is similar to those reported in other countries around the world. In a multi-country study published on 2022, intensification range from 20% in Japan to 64% in Spain, with low rates of adoption of NHT in United Kingdom, Italy, and Japan (Table 3)39.

Table 3. Intensification adoption in HSCPm around the world

| Country | Year | Population | Exclusive ADT (%) | NHT (%) | Chemotherapy (%) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 2019 | 3556 | 79.90 | 3 | 10 | Wallis, 202140 |

| France | 2020 | 254 | 46.50 | 35.80 | 14.60 | Leith, 202239 |

| Germany | 2020 | 179 | 34.10 | 34.10 | 21.80 | Leith, 202239 |

| Italy | 2020 | 155 | 65.80 | 14.20 | 19.40 | Leith, 202239 |

| Japan | 2020 | 125 | 78.4 | 19.20 | 1.50 | Leith, 202239 |

| Spain | 2020 | 173 | 34.10 | 38.20 | 26.60 | Leith, 202239 |

| UK | 2020 | 127 | 47.20 | 12.6 | 40.20 | Leith, 202239 |

| USA | 2021 | 109607 | 50 | 29 | 7 | Heath, 202238 |

|

ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; NHT: novel hormonal therapy. |

||||||

In our context, although the information on the treatment patterns of mHSPC is scarce and not generalizable, the intensification is greater than that reported around the world. This is probably related to access to medicines in our health system. The intensification varies from 60% to 90% depending on the level of complexity and the experience of the center in treating these patients. The implementation of intensification seems to occur more quickly in academic or specialized institutions in the treatment of PCa. However, intensification in non-academic and non-specialized institutions is carried out in 70% with chemotherapy and ADT only without including a NHT, as proposed by the NCCN guidelines24. This may be due to lack of knowledge of the new guidelines, and barriers to access.

Regarding age groups, in reports from the United States, the use of ADT + DOC was lower in patients ≥ 75 years, while the use of ADT + NHT was similar in all age groups. In general, treatment intensification was performed more frequently among patients with bone and/or visceral metastases than among those with lymph node metastases only. However, most patients with visceral metastases, even in recent years, received ADT alone, despite the availability of DOC and NHT41. In our country, we do not have this information in detail, so it would be interesting to carry out studies that allow us to better understand the treatment patterns of mHSPC in Colombia.

Compared to patients with mHSPC, inpiduals with mHSPC incur a greater use of health resources and a significant impact on personal and financial burden42. More effective treatment and management are urgently needed to delay patients with mHSPC from entering the castration resistance phase. This requires, in addition to what has been described, the development of education and awareness programs for physicians to properly identify the risk, manage and refer patients and, in the specific case of mHSPC, intensify therapy earlier.

There are limitations in this review that should be considered when interpreting the information, some of which have been previously described. The data for Colombia in mHSPC are scarce, so the regional information presented as a context may not represent the reality of the disease in the country. In addition, the available sources are highly variable in their reports, so an integrated analysis was not possible beyond an approach to the incidence of mHSPC based on the CAC and Globocan estimates, knowing that a significant underreporting bias might be present.

In addition, the information by subgroup of populations with PCa, the specific clinical and histological characterization, and the treatment patterns constitute a matter of special interest for the adequate analysis of the panorama of PCa in the region. The strengthening of comprehensive and reliable national cancer registries facilitates the development of integrated policies at the national and regional levels for PCa. It is necessary to implement an mHSPC registry because with the new diagnostic tools available, its incidence is expected to increase since hidden lesions not appreciated in conventional images (computed tomography, bone scan) will now be detected.

Conclusion

Our SLR provides an overview of the mHSPC in Colombia. Due to the limited information, it may not accurately reflect the burden of the disease in the country, but it makes it possible to clearly identify the gaps in information regarding this stage of PCa in Colombia. With the data currently available, it is established that men with mHSPC are of great interest for intervention due to the clinical and economic impact of the progression to states of resistance to castration. The landscape described invites us to strengthen interventions for timely screening and effective access to diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of mHSPC, as well as the necessary information for physicians related to the identification and management of this condition.

Funding

Astellas Farma Colombia financed the external research advisory team (EpiThink Health Consulting). The authors declare the research was conducted without any commercial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Conflicts of interest

S. Liliana-Amaya was employed by Astellas Farma Colombia at the time of writing this manuscript. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical considerations

Protection of humans and animals. The authors declare that no experiments involving humans or animals were conducted for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The study does not involve patient personal data nor requires ethical approval. The SAGER guidelines do not apply This study was conducted under ethical norms and adhered to Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Colombia and Law 1581 of 2012 regarding data protection. It was classified as risk-free research as it does not involve patient inclusion or sensible data.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The authors declare that no generative artificial intelligence was used in the writing of this manuscript.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at DOI: 10.24875/RUC.24000051. These data are provided by the corresponding author and published online for the benefit of the reader. The contents of supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors.