Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is defined as any involuntary loss of urine. It can be classified into three main types: (1) Stress urinary incontinence (SUI), which, according to the International Urogynecological Association and the International Continence Society, is defined as “the observation of involuntary leakage from the urethra synchronous with physical effort or sneezing or coughing”1; (2) Urge urinary incontinence, which is reported by the patient as the involuntary leakage of urine accompanied by or immediately preceded by a sudden urge to urinate; and (3) Mixed urinary incontinence, where symptoms of both stress and urge incontinence coexist2,3.

SUI primarily affects women and represents a significant health care and economic burden for society and individuals. It compromises the quality of life and sexual function, increases stress/social isolation, and restricts physical activities4–6. UI contributes to a significant economic burden, with direct costs exceeding $12 billion for women in the United States, surpassing the cost of breast cancer, which is the most common in this population ($8.9 billion)7. In Colombia, costs can be as high as $189,800,000.00 COP8.

In most studies, the prevalence of UI in women varies between 25% and 45%. It gradually increases with age, peaking early, around 50-54 years (coinciding with menopause), followed by a slight decrease or stabilization until age 70, when the prevalence increases steadily2. Regarding the Colombian population, the prevalence of SUI is approximately 8.6%9. SUI is associated with significant risk factors such as advanced age, pregnancy and vaginal childbirth, smoking, obesity, pelvic surgery (hysterectomy), menopause, and high-impact exercise, among others1. It has been shown that Hispanic women are up to 60% less likely to develop urinary incontinence than non-Hispanic white women10.

Regarding treatment, the first line for managing mild to moderate SUI is conservative, implementing behavioral therapies, pelvic floor muscle exercises, and lifestyle optimization. For medical treatment, medications such as selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, such as duloxetine, can be used for 8-12 weeks in patients who do not respond to conservative treatment and those awaiting surgery. Patients requiring surgical intervention have alternatives such as the pubovaginal sling, which involves placing a short graft (8-10 cm) at the bladder neck, with its ends incorporated into the endopelvic fascia and eventually fixed by fibrosis in the retropubic space. Graft types available for this purpose include fascia lata allografts, fascia lata autografts, synthetic grafts, rectus abdominis fascia autografts, dermis allografts, and xenografts11–14.

Autologous fascia slings were commonly used before 1990, but they lost popularity with the advent of minimally invasive synthetic mid-urethral slings. However, severe long-term complications have been observed with these, such as mesh erosion, chronic pelvic pain, and dyspareunia. This has generated controversy and medicolegal implications for surgeons, leading the United States Food and Drug Administration to warn about their use, significantly reducing their availability and use in many countries15. In addition, the European Commission requested the Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks to evaluate the use of synthetic meshes, concluding that their use should only be recommended in cases where conventional surgical procedures have failed16. This has led to the resurgence of natural autologous fascia slings for the surgical treatment of SUI17,18. Cadaveric fascia lata (CFL) slings are attractive due to their lower morbidity, shorter hospital stays, better biocompatibility, and lower risk of erosion post-implantation19. However, there is a clinical practice concern about their use due to the risk of infection and lack of knowledge about their utility. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to synthesize the available scientific evidence on the characterization and outcomes of CFL allografts compared to other available grafts for managing SUI.

Study design

This systematic review of the literature was reported following the PRISMA reporting checklist.

Data sources and search strategy

A literature search was conducted for articles published up to October 6, 2023, in the health field’s two most important electronic databases (Medline-PubMed and EMBASE) without any language restrictions. Initially, terms related to the PICO elements were used, resulting in zero results, so a broader and more sensitive search was decided. Consequently, terms related to the population and interventions were combined: Urinary Incontinence [Free], Pubovaginal Slings [Free], OR Allografts Fascia Lata [Free]. The search algorithms were: ([Urinary Incontinence] AND [Pubovaginal Slings]) AND [Allografts Fascia Lata] and “stress incontinence”/exp AND “allograft”/exp AND (“fascia lata”/exp OR “fascia lata” OR “fascia lata pediculata” OR “femoral fascia”). The final searches were merged and managed for screening in the rayyan.ai web application.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Studies were eligible if: (1) the study population was women with SUI; (2) they used CFL slings; and (3) any epidemiological design. Abstracts from scientific events and letters to the editor were excluded. Initially, two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of all studies identified according to the selection criteria. Full texts of studies that met the selection criteria were subsequently retrieved. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus or consultation with a third independent reviewer.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was created in Microsoft Excel to collect relevant information from the included studies. Two reviewers independently extracted the following data from each study: first author’s name, year of publication, title, objective, design, sample size, intervention (CFL), comparator, outcomes, and main results related to outcomes, and conclusions. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus or consultation with a third independent reviewer.

Risk of bias assessment of included studies

Two authors independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist according to the relevant design20. Each criterion in the JBI checklist was assigned an outcome (yes/no/unclear/not applicable). The total JBI appraisal score was used to classify each review as good, moderate, or low. Quality was assessed on an 11-point scale for cohort studies and systematic reviews (good quality: 9-11 points, moderate quality: 5-8, and low quality: ≤ 4), an 8-point scale for cross-sectional studies (good quality: 7-8 points, moderate quality: 4-6, low quality: ≤ 3), a 6-point scale for narrative reviews (good quality: 5-6 points, moderate quality: 3-4, low quality: ≤ 3), and a 10-point scale for case series (good quality: 8-10 points, moderate quality: 5-7 points, and low quality: ≤ 4 points). Quality was also evaluated in duplicate, with consultation of a third reviewer in case of disagreement.

Statistical analysis

A narrative synthesis was conducted to construct summary tables of the included studies; given their heterogeneity, meta-analysis was not possible.

Results

Identification and selection of studies

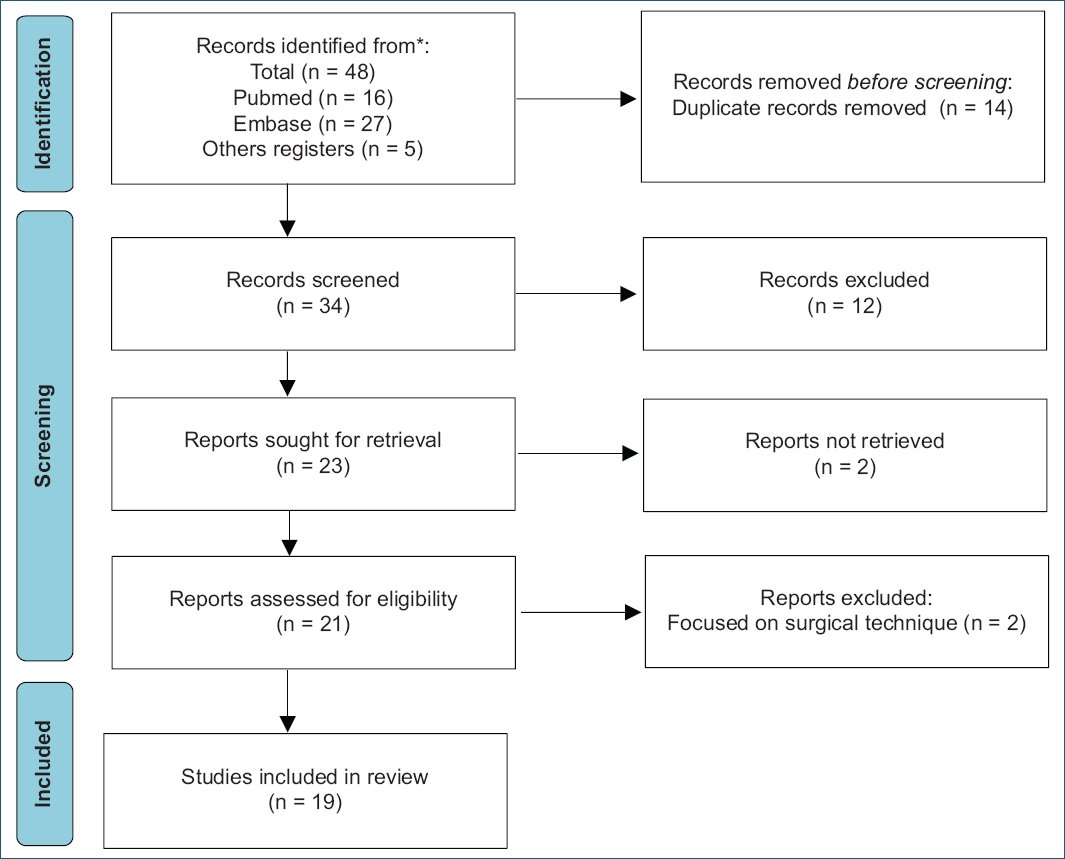

The database searches identified 48 studies, of which 19 (757 participants) met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Study identification via database and records.

Most of the studies were conducted in the United States (n = 14), followed by Canada (n = 2), and three in other countries, each with one study (Belgium, China, and Brazil), between the years 1998 and 2022. Furthermore, most were case series in design (n = 8; 44%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Selected studies

| Authors/year/country | Objective | Study design/sample size | Intervention/comparator | Outcomes | Main results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wright et al.30, 1998, Canada | To evaluate whether allograft fascia is a safe and effective alternative to autologous fascia for pubovaginal sling surgery in women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency. | Retrospective study 92 women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency | Allograft fascia versus Autologous fascia | Overall success rates; Post-operative urinary symptoms vaginal pain or discomfort; post-operative sexual function; operative time; length of hospital stays; duration of post-operative suprapubic tube; number of associated pelvic floor reconstructive procedures | There were no statistically significant differences between the groups regarding overall success rates, incidence of post-operative urinary symptoms, vaginal pain or discomfort, post-operative sexual function, or the number of associated pelvic floor reconstructive procedures. Operative time was significantly shorter in the allograft group (87 min) compared to the autograft group (111 min). Length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in the allograft group (1.67 days) compared to the autograft group (2.48 days). | The study suggests that cadaveric allograft fascia is a safe and effective alternative to autologous fascia for pubovaginal sling surgery in women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Allograft fascia may reduce operative time and length of hospital stay while providing similar outcomes and complications to autologous fascia. |

| Fitzgerald et al.24, 1999, USA | Reporting on the experience with the use of lyophilized and irradiated fascia lata allografts for suburethral sling procedures. | Case series 32 patients with SUI | Suburethral sling surgery with lyophilized and irradiated fascia lata allograft. versus No comparison group | Performance of lyophilized and irradiated fascia lata allografts. | The material failure rate was 20%. In 7 (20%) patients, the allograft was either absent or severely degenerated upon reoperation for persistent or recurrent SUI. | Lyophilized and irradiated fascia lata are used for suburethral sling procedures, but they are associated with a material failure rate of ≥ 20%. Therefore, they are discouraged in this context. |

| Elliott and Boone26, 2000, USA | Provide important information on using cadaveric fascia lata as material for pubovaginal sling procedures in patients with SUI and contribute to the development of evidence-based practice in this area. | Retrospective case series 26 women with SUI | Pubovaginal sling using irradiated and lyophilized cadaveric fascia lata (Tutoplast), terminally irradiated with 25 kGy (2.5 Mrads) of gamma radiation for sterilization as sling material. versus Historical cure rates using rectus fascia. | Symptom improvement, sanitary pad use. | 92% of patients used one or fewer sanitary pads per day. 96% reported significant symptom improvement after surgery. | The continued use of cadaveric allograft for pubovaginal sling procedures in patients with SUI is recommended, given its intraoperative and post-operative advantages. A long-term evaluation of the durability of cadaveric slings compared to autologous fascia is justified. |

| Amundsen et al.37. 2000, USA | Determine whether the use of cadaveric fascia lata material offers success rates similar to rectus fascia. Furthermore, evaluate the infectious morbidity associated with the procedure and post-operative quality of life. | Retrospective cohort 91 women | Placement of a lyophilized allograft pubovaginal sling obtained from a tissue bank and prepared through a patented process (lyophilization, irradiation, and sterilization). versus No comparison group | Quality of life, urinary symptoms, post-operative sanitary pad use, and post-operative complications. | Pre-operative mean daily sanitary pad use was 4.6 ± 3.0. Post-operative use was 1.1 ± 1.4 (p < 0.0001). 63% of patients had resolution of any SUI symptoms. 100% of patients reported no substantial impact on their quality of life. No post-operative complications related to the allograft material were observed. | The use of fascia lata pubovaginal sling allograft is a safe and effective treatment option in both the short and long term. |

| Singla31, 2000, USA | Synthesize the available evidence to date on interventions with cadaveric fascia lata pubovaginal sling. | Narrative review Six studies | Cadaveric fascia lata pubovaginal sling versus Synthetic slings, autografts | Safety, efficacy, durability, complications, cost | The main complication after a pubovaginal sling is de novo detrusor instability in 10-40% of cases. Prolonged urinary retention may occur in 5% of patients; ureteral, bladder, or vaginal injuries are rare. Both allografts and autografts were equally well tolerated, with no infection or erosion of the sling material observed. Overall continence rates were comparable between the two groups: 98% for allografts versus 94% for autografts.

Allografts resulted in an 83% reduction in average post-operative pain, the operation took half the time, and the hospital stay and convalescence period were also significantly shorter. Operation duration and hospital stay were reduced from 151 to 115 min (p = 0.03) and from 2.1 to 1.4 days (p = 0.005), respectively. Unit cost savings were $750/patient using cadaveric fascia. No complications were observed during the median follow-up of 8 months |

The results of the narrative review support the safety, efficacy, and durability of fascia lata; in early follow-up, the results are comparable to the autograft fascia sling, but long-term results are still awaited. The use of processed fascia poses an insignificant risk of disease transmission. To date, no adverse outcomes have been reported. |

| Choe et al.21, 2001, USA | Using the Instron tensiometer, compare the biomechanical properties of allografts, autografts, and synthetic materials used in sling surgery. | Cross-sectional analytical study. 20 women undergoing vaginal prolapse surgery. | Cadaveric allograft slings versus Synthetic and autologous slings | Tensile strength. | Full-strip sling: Cadaveric allografts showed the highest tensile strength, followed by synthetic and autologous tissues (p < 0.05). Suture-with-patch sling: Synthetic and dermal tissues (autograft and allograft) had higher tensile strength, followed by cadaveric fascia lata, rectal fascia, and vaginal mucosa (p < 0.05). The tensile strength of full-strip slings was greater than that of suture-with-patch slings in all groups (p ≤ 0.001). | Within each graft subgroup, regardless of the material evaluated, the full-strip sling has greater tensile strength than the suture-with-patch sling. Cadaveric fascia lata shows a significantly higher mean maximum load to failure. |

| Vereecken and Lechat22, 2001, Belgium | Report on the use of cadaveric fascia lata slings in the treatment of intrinsic sphincter deficiency and describe the authors’ experience with this material in severe incontinence cases. | Case series Eight women underwent urethroplasty with a cadaveric fascia lata sling. | Urethroplasty with a cadaveric fascia lata sling. versus No comparison group | Complications, reinterventions, material-related issues | The cadaveric fascia lata sling was well-tolerated and resulted in good continence without obstructions. The use of cadaveric fascia allograft had a lower risk of erosion and rejection compared to synthetic materials. | The cadaveric fascia lata sling is a safe and effective treatment option for women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Cadaveric fascia lata showed lower morbidity, shorter hospital stays, reduced risk of complications, and a high likelihood of long-term success. |

| Huang et al.25, 2001, China | Evaluate the efficacy and safety of using fascia lata allograft in pubovaginal sling surgery for SUI. | Retrospective case series 18 women with SUI | Pubovaginal sling surgery using gamma-irradiated and solvent-dehydrated human fascia lata as sling material. versus Previous studies using different sling materials. | Subjective success rate, Failure rate | Mean subjective success rate of 82.5% (range 50-100%) with fascia lata allograft. The failure rate was 27.8%, with total recurrence of incontinence within 3-6 months post-surgery. | Gamma-irradiated and solvent-dehydrated fascia lata allografts are not reliable for use in pubovaginal sling surgery. Their high failure rates within a short period prohibit their use in the treatment of SUI. |

| Soergel et al.32, 2001, USA | Report on the poor surgical outcomes observed after using fascia lata allografts in pubovaginal slings to treat intrinsic urethral sphincter deficiency. | Cross-sectional analytical study 12 patients with genuine stress incontinence complicated by intrinsic sphincter deficiency and urethral hypermobility. | Placement of pubovaginal sling for incontinence treatment. The sling material used was fascia lata allografts harvested from cadavers and processed by three companies. versus Rectal autologous fascia sling. | Cure rate | 33.3% of patients with cadaveric fascia lata had effective treatment, compared to 78.8% with rectal autologous fascia. | Fascia lata allografts are a poor choice for pubovaginal slings. |

| Carbone et al.33, 2001, USA | Evaluate the efficacy and safety of the pubovaginal sling procedure using cadaveric fascia and bone anchors to treat SUI. | Retrospective cohort 154 patients | Pubovaginal sling procedure. versus No comparison group. | Efficacy, outcomes, complications. | 39.6% had moderate-to-severe recurrent SUI during 10 months of follow-up. 26 patients underwent a second pubovaginal sling intervention at 9 months (range 3-15) after the first procedure, with a recovery rate of 16.9%. All of these patients had fragmented, attenuated, or absent cadaveric allograft fascia. | Recurrent SUI is directly related to the failure of the cadaveric fascia anchored to the bone. Therefore, the study institution discontinued the use of cadaveric fascia allografts in all pubovaginal slings. |

| Walsh et al.23, 2002, USA | Evaluate and quantify the efficacy of cadaveric fascia lata as allograft material in pubovaginal slings for SUI. | Case series 31 women with SUI | Pubovaginal sling surgery with cadaveric fascia lata allograft. versus No comparison group. | Surgical time, blood loss, hospital stay, and surgical complications. | At 13.5 months of follow-up, 93% of patients had complete resolution of SUI. At 1 year, 94% of patients no longer had symptoms of overactive bladder. The severity of leakage and storage symptoms was significantly lower (p < 0.002). | The pubovaginal sling using cadaveric fascia lata allograft is a highly effective and safe surgical method (shorter surgical time, shorter hospital stay, and reduced complications) for resolving SUI. Storage symptoms and patient satisfaction were significantly improved at 1 year using cadaveric fascia lata. |

| Flynn and Yap27, 2002, USA | Evaluate the efficacy and safety of using cadaveric fascia allograft versus autologous fascia graft in women undergoing pubovaginal sling procedure for SUI. | Case series 134 women with SUI | Sling made from autologous tissue. versus Sling made from allografts | Surgical success, post-operative complications; patient satisfaction; post-operative pain and disability; overall cure rate; recurrence of symptoms. | The use of cadaveric fascia allograft as an alternative to autologous fascia resulted in a significant decrease in post-operative pain and disability (p < 0.05). No statistical differences existed in the overall stress and urgency incontinence cure rate between the allograft and autograft groups (p = 0.42). There was no difference in the total number of recurrent SUI cases (p = 0.58). | The use of cadaveric fascia allograft as an alternative to autologous fascia for pubovaginal sling significantly reduces post-operative pain and disability without compromising efficacy at 2 years. |

| O’Relly and Govier34, 2002, USA | Investigate the mid-term failure rate using cadaveric fascia lata in the treatment of recurrent SUI. | Case series eight patients | Sling with frozen cadaveric fascia lata | Type of fascia, surgical technique, pre-and post-operative urodynamic, surgical history, and medical comorbidities. | All patients experienced recurrent SUI, with no urgency incontinence or detrusor instability. The mean time to failure was 6.5 months (range 4-13). The group of patients with cadaveric fascia lata had a failure rate of 7%. Two patients experienced failure within the 1st month. | A higher-than-expected mid-term failure rate was identified using frozen cadaveric fascia lata. It was concluded that graft failure is the most likely cause of these mid-term failures, which have not been observed in autologous cases. Longer follow-up and larger numbers are needed to determine the extent of the problem and which patient characteristics are relevant when selecting cadaveric grafts. |

| Amundsen et al.29, 2003, USA | Present a series of urethral erosions following pubovaginal sling procedures due to synthetic and non-synthetic materials. Discuss the management and outcome of continence. | Case series Nine patients with urethral erosion | Non-synthetic slings (allograft fascia and autograft fascia) versus Synthetic slings (ProteGen and Polypropylene) | Measurement of pad usage and recurrence of symptoms. | At 30 months post-procedure, nine women presented with some manifestation of voiding dysfunction, such as urinary retention in four, urgency incontinence in three, and mixed incontinence in two. Urinary retention resolved in three patients, and urgency incontinence resolved in four. SUI persisted in two of the three patients in the synthetic group, while no patient in the non-synthetic group had recurrent SUI. No recurrent urethral erosions or fistulas occurred in either group. | Urethral erosion after a pubovaginal sling procedure can occur regardless of the sling material. However, recurrent SUI is not an inevitable outcome of treating urethral erosion following a pubovaginal sling intervention. |

| Almeida et al.35, 2004, Brazil, USA | Compare the technique and outcomes of patients treated with allografts or autografts as pubovaginal slings. | Cohort study Group A (allograft): 30 women. Group B (autograft): 30 women. | Cadaveric fascia lata allograft versus Autologous fascia lata | Cure rate; adverse outcomes; surgical time; and hospital stay. | Group A: 40% of patients were cured, and 28% had improved at an average follow-up of 36 months (22-44 months). Group B: 70% of patients were cured, and 20% improved at an average follow-up of 33 months (24-41 months). There were no adverse outcomes related to sling erosion or infection. The mean time for allograft sling placement was 62 min, whereas for sling placement requiring fascial harvest was 81 min (p < 0.05). The mean hospital stay was shorter with the allograft (1.25 days) compared to the autograft (2.48 days) (p < 0.05). | The frozen cadaveric fascia lata sling is safe, requires shorter surgical time and hospital stay, but the 3-year continence rate is lower than that of the autograft surgery. The use of allografts was associated with shorter surgical and hospital stay times compared to an autograft, but the 3-year continence rate was lower in the autograft group. |

| Owens and Winters28, 2004, USA | Provide information on the use of cadaveric dermal allograft Duraderm as sling material for SUI. | Retrospective cohort 25 patients with SUI. | Duraderm dermal grafts of 2 × 12 cm. versus No comparison group. | Procedure effectiveness; patient satisfaction; symptom reduction | At 6 months, 68% of patients were dry, 24% improved, and 8% failed. At 14.8 months, 32% of patients were dry, 36% improved, and 32% experienced Duraderm sling failure. The average post- operative pad use was 1.4. 76% of patients were satisfied with the surgical outcome. | The use of Duraderm allograft reported an initial success rate of 68%. However, this decreased to 32% at 14.8 months Graft degeneration after using cadaveric fascia lata may be possible following the implementation of cadaveric dermis. |

| Gomelsky and Dmochowski19, 2005, USA | Evaluate the outcomes of available sling materials in the context of biocompatibility and tissue acceptance. | Narrative Review 16 studies | Non-synthetic slings versus synthetic slings | Not applicable. | Allografts eliminate the time and morbidity associated with the harvesting of autologous fascia. In addition, greater biocompatibility and a lower erosion risk have been observed compared to synthetic slings. There is a risk of disease transmission with the use of allograft tissues. | The processing of cadaveric fascia lata is not standardized. Its use may be associated with high short and medium-term failure rates. The incorporation of cadaveric allografts in sling surgery has reduced operative time, the morbidity of autologous fascia harvesting, and shortened post-operative recovery. Solvent-dehydrated cadaveric fascia lata is more durable than lyophilized fascia. |

| Pianezza et al.38, 2007, Canada | Evaluate long-term patient satisfaction after pubovaginal fascia lata cadaveric sling surgery using the UDI and the IIQ short form | Case series 37 patients | Pubovaginal fascia lata cadaveric sling. versus No comparison group. | Quality of life, patient satisfaction | The mean UDI score was 75.8, and the mean IIQ-7 score was 21.4. There were no differences in the mean IIQ-7 score for patients with more than 4 years of follow-up compared to the entire group (28.8, p = 0.22). In contrast, the mean UDI score for patients with more than 4 years of follow-up was higher than that of the entire group (99.1, p = 0.04). The UDI subscale analysis revealed that patients mainly complained of irritative and stress symptoms rather than obstruction/discomfort (p < 0.01). Patients with pre-operative mixed incontinence had higher mean UDI and IIQ-7 scores than patients with pure stress incontinence (96.7 vs. 58.0, p = 0.04; 32.5 vs. 11.9, p = 0.03). | Long-term global scores for evaluating quality of life (IIQ-7) were good, and UDI scores were satisfactory after pubovaginal sling surgery. Patients with pre-operative mixed incontinence are at higher risk of post-operative dissatisfaction. |

| Cabrales et al.36, 2022, USA | Describe the available data on outcomes, complications, and durability of allograft sling materials used to treat SUI. | Systematic review 14 studies | Allograft fascia lata; autograft fascia lata; cadaveric dermis; autograft rectus fascia; synthetic; xenograft versus No comparison group | Follow-up, cure, de novo incontinence, operative time, hospital stay, complications. | Success rates using allograft material ranged from 68% to 98%. Two studies demonstrated a shorter lifespan for cadaveric fascia. Cadaveric fascia lata had shorter operative times, shorter post-operative hospital stays, and lower infection rates. Procedures with allografts ranged from 62 to 87 min, while procedures with autografts averaged between 82 and 119 min. Success was defined as the use of one or fewer pads per day. Some studies have evidenced the recurrence of SUI symptoms within 3-6 months | Cadaveric allograft fascia has proven to be an effective option in terms of success rates and satisfaction scores compared to other materials. The allograft procedure offers shorter operations, shorter post-operative hospital stays, and a low risk of wound complications. Limitations of the reported data include variation in follow-up times, single-institution series, and different definitions of success. Uncertainty about the durability of allografts prevents their standardization. |

|

SUI: stress urinary incontinence; UDI: urogenital distress inventory; IIQ: incontinence impact questionnaire. |

||||||

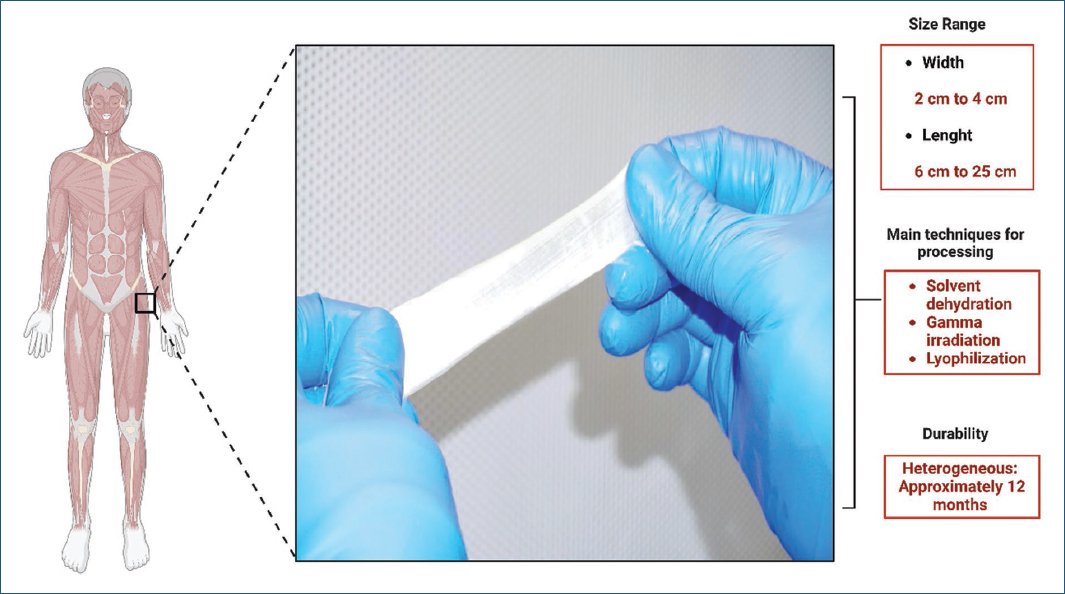

Characterization of CFL

SIZE

Most of the included studies reported graft dimensions. Choe et al.21 considered a size of 2 × 5 cm to be the most commonly used in clinical practice. Gomelsky et al.19 mentioned that the lengths of CFL slings ranged from 4 to 25 cm. Vereecken et al.22 mentioned a 2-3 cm fascia lata width. Walsh et al.23 used a 9-11 cm size. Fitzgerald et al.24 used dimensions of approximately 3 × 10 cm. Huang et al.25 used a length of 7 × 2 cm. Elliot and Boone26, Flynn and Yap27, and Owens and Winters28 employed a size of 2 × 12 cm. Amundsen et al.29, Wright et al.30, and Singla31 used dimensions of 2 × 15 cm. Soergel et al.32 used sizes of 2 × 10 cm. Carbone et al.33 used dimensions of 2 × 6 cm as this size was ideal for providing support and not placing excessive tension on the urethra and bladder neck when anchored laterally to the pubic bone.

PROCESSING

Many studies also included the processing of CFL in their reviews.19,21,24–27,31–33 Gomelsky and Dmochowski19 conducted a narrative review of the literature, finding that the two main techniques for CFL processing are solvent dehydration and lyophilization. Both techniques require 30 min of rehydration in saline solution before implantation. In addition, they highlighted the lack of standardization in CFL processing in their research. Other researchers used gamma-irradiated CFL processing up to 1.5-2.5 Mrads (15-25 kGy) for tissue sterilization21,24,27,31–33. Authors like Fitzgerald et al.24 reported up to 20% material failure rates when processed by lyophilization or subjected to irradiation. Huang et al.25 had up to 27.8% failure rates if processed by solvent dehydration or gamma irradiation.

DURABILITY

Regarding the durability of the CFL sling, Choe et al.21 and Vereecken and Lechat22 showed greater tensile strength in cadaver allografts compared to synthetic and autologous tissues (p < 0.05). Regarding long-term durability, some authors have followed CFL for 12 months, finding consistent material fragmentation failures of up to 38%33.

On the other hand, authors such as Fitzgerald et al.24 and Huang et al.25 mentioned the poor performance of allograft slings according to their processing. Fitzgerald et al.24 documented fascia autolysis of up to 20% in those processed by lyophilization or irradiation. Huang et al.25 reported a failure rate of up to 27.8% when using gamma-irradiated and solvent-dehydrated allograft fascia lata. Other authors19,34 observed early failure rates of up to 20% in frozen-processed allograft slings19.

Regarding durability related to rejection or infection transmission risk, Gomelsky and Dmochowski19 and Vereecken and Lechat22 argue that allografts have more excellent biocompatibility and a lower erosion risk than synthetic slings. In addition, Gomelsky and Dmochowski19 point out probable factors influencing CFL sling durability, such as host reaction to the graft, accelerated immunity, and autolysis. Almeida et al.35 and Singla31 compared outcomes between patients treated with allograft and autograft, finding no adverse events regarding material erosion or infection, concluding that CFL use is safe for patients with an insignificant risk of disease transmission. Cabrales et al.36 observed lower infection rates with CFL use.

Outcomes

Outcomes were evaluated in various ways, including the number of daily pads used, quality of life, symptom frequency, and patient satisfaction postoperatively23,27,28,30,35.

DECREASE PADS

The success rate was determined by the number of daily pads used, as noted in several studies23,26,28,36,37. The daily average of pads used for managing urinary incontinence ranged between 3.2 and 4.623,26,37. A significant decrease in pad use was observed immediately after surgery, with an average of 1 ± 1.4 pads (p < 0.0001)26,37, reaching as low as 0.8 pads at 1 year of follow-up23. Flynn and Yap27 classified urinary incontinence outcomes by the number of pads used in 24 h, categorizing them as cured (0 pads), improved (1 pad), and failed (more than one pad). The mean post-operative pad use was 0.7 ± 1.3. Up to 29% of patients still required one or more pads daily.

QUALITY OF LIFE AND PATIENT SATISFACTION POSTOPERATIVELY

Authors such as Almeida et al.35 showed that most participants (87%) did not consider urinary incontinence a significant impact on their quality of life, whereas Walsh et al.23 observed a reduction in symptom frequency at 4 months and 1-year post-surgery. However, variability in patient satisfaction perception was observed among different studies. Flynn and Yap27 identified lower satisfaction in patients who received allografts, although this was not significant (p = 0.05). However, other studies, such as that of Owens and Winters28, reported a 90% satisfaction rate at 6 months postoperatively with allograft use, which decreased to 60% at 14 months. In addition, Pianezza et al.38 demonstrated satisfactory scores in symptom reduction with CFL use during 2 years of follow-up.

PATIENT SATISFACTION POSTOPERATIVELY

Symptom recurrence was considered one of the outcomes in various studies. Huang et al.25 observed complete urinary incontinence recurrence in five patients (27.8%) within 3-6 months. In contrast, Flynn and Yap27 found no significant difference in recurrence between allograft and autograft use (eight and seven cases, respectively; p = 0.58).

The principal characteristics and findings of the CFL can be found in figure 2.

Figure 2. Main characteristics and findings of the cadaveric fascia lata.

Quality of the studies

The quality of the included studies was mainly moderate (n = 9; 47.36%). In addition, eight studies (42.10%) were of good quality, whereas two were considered low quality (10.52%). The low quality of the mentioned studies was due to issues in participant selection, sample description, and statistical analysis (Table 2).

Table 2. Risk of bias assessed by the JBI

| Author/year | JBI checklist items for cross-sectional studies | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear inclusion criteria | Description of study subjects and setting | Exposure measurement | Measurement criteria | Identification of confounding factors | Strategies for confounding factors | Outcomes measurement | Proper statistical analysis | Overall rating | |||||

| Choe et al.21 (2001) | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Moderate risk | ||||

| Soergel et al.32 (2001) | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Moderate risk | ||||

| Author/year | JBI checklist items for cohorts | ||||||||||||

| Two groups similar and recruited from the same population | The exposures measured similarly to assign people to both exposed and unexposed groups | Exposure measurement | Identification of confounding factors | Strategies for confounding factors | Groups/participants free of the outcome | Outcomes measurement | Follow-up time | Follow-up complete. If not, they describe the reasons | Strategies to address incomplete follow-up utilized | Proper statistical analysis | Overall rating | ||

| Almeid et al.35 (2004) | U | Y | U | N | N | U | N | Y | N | N | N | High risk | |

| Amundsen et al.37 (2000) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Moderate risk | |

| Author/year | JBI checklist case series | ||||||||||||

| Clear inclusion criteria | Condition measured in a standard. | Valid methods used for identification of the condition | Consecutive inclusion of participants | Complete inclusion of participants | Clear reporting of the demographics of the participants | Clear reporting of clinical information | Outcomes or follow-up time clear | Clear reporting of the presenting site (s)/clinic (s) demographic information | Proper statistical analysis | Overall rating | |||

| Vereecken et al.22 (2001) | Y | N | N | Y | U | N | Y | Y | N | N | High risk | ||

| Walsh, et al.23 (2002) | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Moderate risk | ||

| Author/year | JBI checklist case series | ||||||||||||

| Clear inclusion criteria | Condition measured in a standard. | Valid methods used for identification of the condition | Consecutive inclusion of participants | Complete inclusion of participants | Clear reporting of the demographics of the participants | Clear reporting of clinical information | Outcomes or follow-up time clear | Clear reporting of the presenting site (s)/clinic (s) demographic information | Proper statistical analysis | Overall rating | |||

| Fitzgerald et al.24 (1999) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Moderate risk | ||

| Huang et al.25 (2001) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Low risk | ||

| Elliot and Boone26 (2000) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Low risk | ||

| Flynn and Yap27 (2002) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low risk | ||

| Owens and Winters28 (2004) | U | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Moderate risk | ||

| Amundsen et al.29 (2003) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Moderate risk | ||

| Wright et al.30 (1998) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Low risk | ||

| Carbone et al.33 (2001) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Low risk | ||

| O’Reilly and Govier34 (2002) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Low risk | ||

| Pianezza et al.38 (2007) | Y | Y | Y | U | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Moderate risk | ||

| Author/year | JBI checklist textual evidence: narrative | ||||||||||||

| Generator of the narrative is credible or appropriate source | Relationship between the text and its context explained | Narrative presents the events using a logical sequence | Similar conclusions to those drawn by the narrator | Conclusions flow from the narrative account | Consider this account to be a narrative | Overall rating | |||||||

| Gomelsky and Dmochowski19 (2005) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low risk | ||||||

| Singla31 (2000) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low risk | ||||||

| Author/year | JBI checklist items for systematic reviews | ||||||||||||

| Review question clearly and explicitly stated | Inclusion criteria appropriate for the review question | Search strategy appropriate | Sources and resources used to search for studies adequate | Criteria for appraising studies appropriate | Critical appraisal conducted by two or more reviewers independently | Methods to minimize errors in data extraction | Methods used to combine studies appropriate | Likelihood of publication bias assessed | Recommendations for policy and/or practice supported by the reported data | Specific directives for new research appropriate | Overall rating | ||

| Cabrales et al.36 (2022) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Moderate risk | |

|

N: no; Y: yes; U: nuclear. |

|||||||||||||

Discussion

CFL has been considered in recent years as a potential substitute for synthetic materials and non-synthetic tissues for various surgical procedures19. Our literature review shows the use of cadaveric allografts with dimensions generally ranging from 2 cm in width up to 25 cm in length for the surgical treatment of SUI. CFL could be an alternative for pubovaginal sling procedures in women with SUI, as some studies have shown a reduction in operative time, hospital stay, and complications compared to other available grafts. However, the reported evidence is heterogeneous, with small sample sizes, short follow-ups, low-level epidemiological designs for assessing efficacy/safety, and moderate quality.

The success or failure of CFL allografts depends on several factors, such as size, processing, and durability. The three main CFL processing techniques are solvent dehydration, gamma irradiation, and lyophilization. Although the processing method used can influence the tensile strength of the allograft bands21, there is currently a need to standardize this process19, leading to contradictory results in different studies21,24,27,31–33. While authors such as Fitzgerald et al.24 and Huang et al.25 reported material failure rates ranging from 20% to 27.8% when processing CFL by solvent dehydration, lyophilization, or irradiation, the sample sizes used in their investigations do not allow for generalizing the results. The recipient’s immune system specifics likely influenced these findings19.

The results regarding the durability of CFL allografts are also heterogeneous. Different authors documented alterations in allograft durability19,24,25. Carbone et al.33 found up to 38% material fragmentation rates during a 12-month follow-up. However, authors like Walsh et al.23 reported symptom resolution in 93.5% of patients at 13.5 months follow-up, which is also related to CFL durability. Although it has been thought over the years that CFL has lower durability and biocompatibility due to its high risk of disease transmission19, all cadaveric allografts undergo thorough serological screening, with the estimated risk of HIV transmission being one in 8 million people39. Other factors, such as host reaction to the graft, accelerated immunity, and autolysis, may be directly related to material durability19.

The outcomes associated with CFL use have mainly been satisfactory. Studies such as those by Walsh et al.23 and Elliot et al.26 showed cure rates above 70% even at 13.5 and 15 months follow-up, respectively. In general, most studies considered a successful surgical procedure based on the number of daily pads used postoperatively and the reduction of SUI symptoms over time. In addition, the decrease in daily pad use was associated with patient satisfaction, with the CFL surgical procedure being recommended by up to 96% at 15 months follow-up26.

This study has several strengths and limitations. Although a more specific rather than sensitive search was prioritized, the found articles answered the established research question, whereas broader searches yielded zero results or identified titles that did not answer the research question. As with all systematic reviews, we are prone to publication bias; however, the search terms were related to the two most important topics in this review (population and intervention). It is also relevant to consider that the quality of the individual studies included in this review was moderate, with small sample sizes, short follow-ups, and epidemiological designs inadequate for evaluating the efficacy and safety of CFL allografts for the surgical treatment of SUI. An advantage of this research is that it includes the characterization of CFL in terms of size, processing, and durability instead of limiting it only to durability and outcome effects.

In conclusion, there are divergent findings regarding the characteristics and efficacy of CFL allografts for managing SUI; however, these allografts have been considered an alternative for managing this condition in recent years. Some studies have shown improved patients’ quality of life, finding acceptable satisfaction levels and positive recommendations after surgery. Other studies observed that incorporating CFL significantly reduces hospital stays, complications, and satisfactory success rates. However, the evidence is primarily from observational studies with short follow-ups and limited sample sizes. Future research should focus on designing experimental or quasi-experimental studies with long-term follow-up and adequate sample sizes to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CFL as a therapeutic option for the surgical management of SUI.

Funding

The authors declare that this work was carried out with the authors’ own resources.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical considerations

Protection of humans and animals. The authors declare that no experiments involving humans or animals were conducted for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The authors have followed their institution’s confidentiality protocols, obtained informed consent from patients, and received approval from the Ethics Committee. The SAGER guidelines were followed according to the nature of the study.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The authors declare that no generative artificial intelligence was used in the writing of this manuscript.